Sonya asked a question that is so important to acknowledge when we’re working to cultivate student agency and ownership over their learning:

How do you “trust students to take control of their own learning” when some learners set the bar so ridiculously low? Serious question. Some kids want to do amazing things. Others are satisfied with the minimum possible effort. How do you coach more out of them? #mypchat #agency

— Sonya terBorg (@terSonya) November 26, 2018

This is different from non-compliance. Non-compliance asks, “how can we get them to do what we ask?” And interestingly enough, for many students, non-compliance issues are often resolved when we shift to the agency-based question that Sonya’s tweet is really about: “How can we inspire students to own their learning?”

But what about when they do comply, and they do take some ownership of their learning, but, as Sonya writes, they “are satisfied with the minimum possible effort?” Here are a few thoughts.

1. Partner with parents. It’s entirely possible that if you just ask, “What have you found motivating for your child?” you’ll find the parents have been at a loss, too. But you might find more success if you try asking something more specific, such as, “What are the top 3 topics that make your child light up?” or “Can you share with me a time when your child was excited to take the lead on something?” This is also an important step to take to check if there might be something bigger going on in the student’s life that is making learning a low priority.

2. Hold regular conferences. I appreciated the details of what makes a conference effective in the recent post by Lanny Ball, “What to do when a writer doesn’t say much?” It’s geared toward writing conferences, but the same qualities can be applied to any kind of conference feedback:

-

“Happens in the moment

-

Specific and calibrated

-

Focused and honest

-

Offers one (maybe two) practical tip(s)

-

Lays out a plan for follow-up

-

Demands a high level of agency from the student”

3. Demystify coming up with ideas. For many students, coming up with an idea can seem like something only those people can do. Help them demystify this by showing them process, process, process. Talk about your own process. Highlight peer process. Share experts’ process. Julie Faltako’s “The Truth About the Writing Process” below is a great example of this (as is her Twitter account, as she regularly turns to others for ideas). And of course, keep a chart of strategies nearby for when we get stuck!

I also love “Where Do Ideas Come From” by Andrew Norton

4. Use “Must, Should, Could” for time planning with exemplars. I absolutely love David Gastelow’s “Must, Should, Could” chart with his young students.

For students who struggle with coming up with ideas, I would definitely provide a menu from which they can select, hopefully gradually opening up over time as they become confident.

5. Expand their knowledge base & sense of self-discovery.

I love inspirational videos like the ones below–I often include them in the provocation posts I write. They help lift us out of the rut of the everyday and help us glimpse issues and passions we might not have even considered. Sharing this kind of work with students, and then finding opportunities to research deeper, might help provide the knowledge base that will awaken a student to a sense of his/her own capacity.

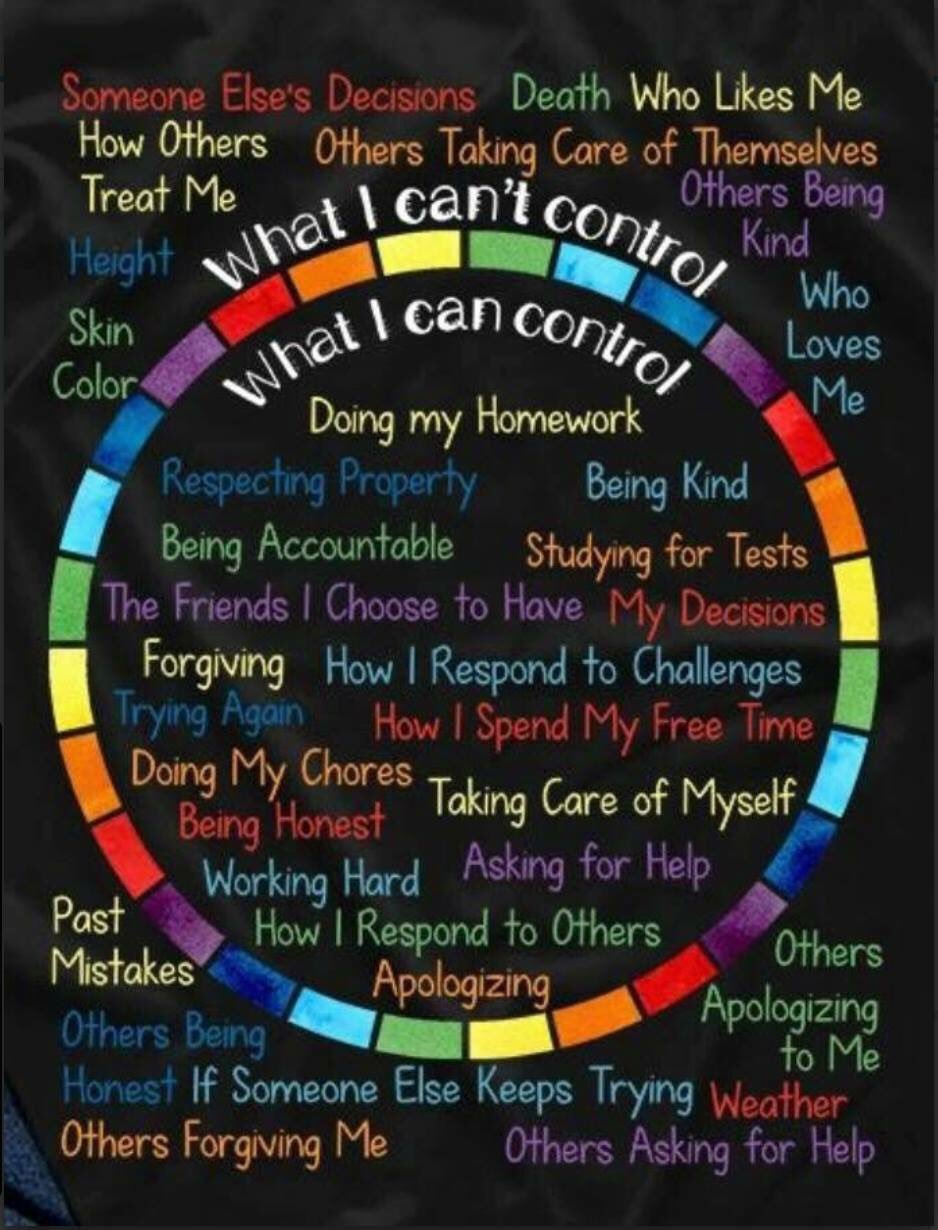

Speaking of knowledge, check out this simple but illuminating visual from Margaret (Maggie) Lewis in Sonya’s thread:

It’s about having a conversation. Putting agency w/Ss to think about how challenging something might be;hence, placing motivation/ power with them. It is a tool we continually reference as a conversation starter in my classroom. Can easily be adapted! pic.twitter.com/TaQWiPzV5P

— Margaret(Maggie) Lewis (@msmargaretlewis) November 28, 2018

None of the above is foolproof. Working with human beings is messy and will requires serious trial-and-error. As Alfie Kohn recently wrote about motivation:

“Working with people to help them do a job better, learn more effectively, or acquire good values takes time, thought, effort, and courage.”

It’s why we need each other in this process! If you have additional strategies or resources, I’m sure we’d all be grateful if you could add to the list!

featured image: DeathToTheStockPhoto